Dyslexia and Reading

Mrs Patricia Spencer (Oak Hill, Nyon) and Dr Jennie Guise (Dysguise, UK) answer parent and teacher questions about reading skills, dyslexia and how best to assist students who learn differently.

What do we know?

Learning to read is often an enjoyable and absorbing skill that many children develop with little inconvenience or bother. However, unlike learning to talk, learning to read and write is not a ‘natural’ or automatic process (Wolf, 2000). As a result, ‘breaking the code’ is a frustrating and exasperating process for some students that gradually serves to undermine self-confidence and limits their access to grade appropriate curriculum. Therefore, understanding the process of how children acquire good reading skills continues to interest (and infuriate!) a wide section of the population. However, effective reading skills are vital twenty first century competencies – their relevance has never been more important.

What are the foundation skills of reading?

Regular exposure to a variety of literature and positive encouragement to enjoy reading is a good starting point for any child. In addition, the essential ‘taught’ elements of literacy development include the five pillars of reading (Sousa, 2005, NICHD, 2000):

- Phonemic Awareness (focusing on the sounds word-parts make)

- Phonic Knowledge (connecting sounds and letter combinations)

- Reading Fluency (reading/understanding at an appropriate pace)

- Vocabulary (continually building word knowledge)

- Comprehension (understanding/inferring/predicting and making connections about the text)

How many children struggle to develop reading skills?

Unfortunately, acquiring core reading skills is challenging for many students at primary level. Research (Shaywitz, 2008, Moats, 2017) suggests that approximately 10-15% of these children may have dyslexia type challenges.

What is dyslexia?

Dyslexia is a lifelong, language-based, learning difference that affects an individual’s ability to develop reading, writing and spelling skills and can frequently co-occur with other learning differences.

Individuals with dyslexia striving to develop appropriate literacy milestones often unexpectedly fail to develop the foundation skills in language. These ‘gaps’ may be related to phonological awareness (rhyming/matching sounds), phonic knowledge (enunciating correct phonemes/matching them with the correct letters), the alphabetic principle (acquiring correct letter/sound correspondence), orthography (recognising patterns and conventions of print), developing age appropriate vocabulary or having sufficient comprehension of the text they are reading or are listening to. Working memory and/or processing speed may also affect how quickly students acquire foundation language skills. In addition, these individuals may also have challenges with spelling, writing and mathematical tasks.

Does dyslexia only affect reading?

No – dyslexic type difficulties may also affect an individual’s capacity to spell, write, remember sequences, complete math problems or express themselves verbally. The issues often overlap.

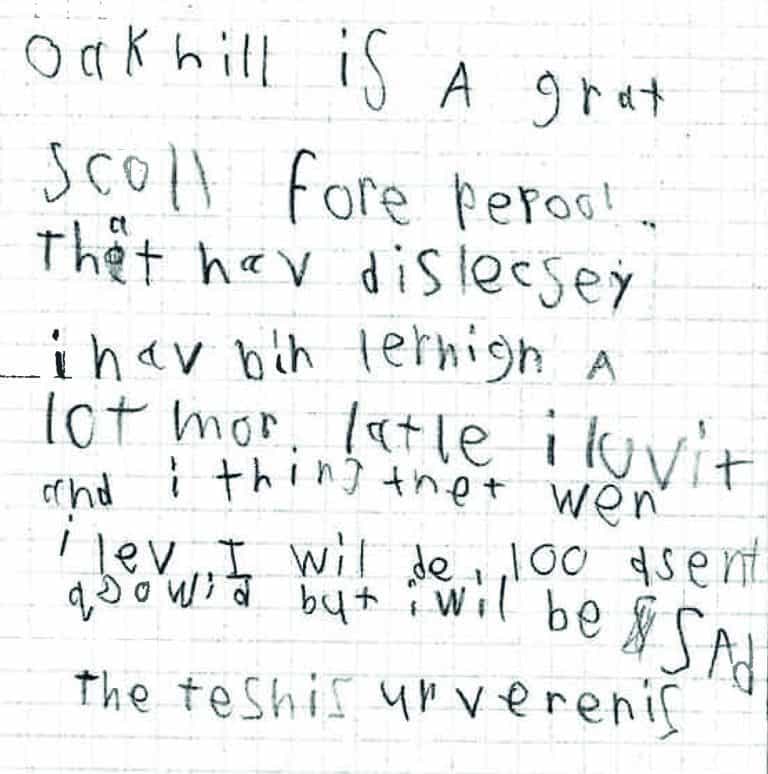

Isn’t dyslexia just reversing letters?

Dyslexia is far wider than this definition! However, it is true that some students may reverse letters at an age beyond their peer group. Parents/teachers interested in finding out more about whether a child has dyslexia, or not, will benefit from carefully observing reading/writing work completed by the student over a few sessions.

It is also helpful to monitor strengths/challenges across a variety of areas, including assessing the child’s:

- Oral language skills

- Writing ability

- Spelling accuracy

- Sequencing skills

- Breadth of vocabulary

- Short/long-term memory

- Their ability to read familiar/unfamiliar words.

This information can then help the parent determine if further screening, or testing, is needed (e.g. with a learning support teacher, speech therapist, psychologist etc)..

What testing might a psychologist conduct?

To determine a child’s overall abilities, educational psychologists often conduct a WISC-V (Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, 5th Edition) to assess a child’s cognitive profile. The subtests in the WISC-V are drawn from five areas: verbal comprehension, visual-spatial ability, fluid reasoning, working memory, and processing speed. The tests are not reliant on reading or writing and are designed to indicate a child’s reasoning abilities and processing.

Alongside this, a WIAT-III (Wechsler Individual Achievement Test, 3rd Edition) is often administered. This test aims to determine achievement levels in literacy and numeracy. After WIAT testing has been completed, results can then be compared with the WISC-V scores, because these two tests are co-related and help the psychologist establish if the child is achieving/performing at levels comparable to their cognitive ability.

After the assessment is complete, a detailed report is written for the parent, explaining the testing. WISC and WIAT scores, therefore, provide information that can help identify if a child is reaching his/her potential. In addition, the results obtained are useful because they can identify areas of strength, as well as areas of relative difficulty that were not previously considered.

Various subtests may show an individual is unexpectedly behind in academic tasks. There may also be ‘spikes’ in an individual’s achievement levels – often an indicator of dyslexic type differences. Finally, a range of recommendations are often provided by the assessor, to help guide parents with best practice and next steps.

What age should I get my child assessed if I have concerns?

Around 7 or 8 years of age is a good time to start investigating if a child is finding it difficult to develop literacy and numeracy skills.

If we leave things as they are, won’t the child just catch up with other children in the class?

Well-meaning adults may feel a child will ‘grow out’ of their difficulties with language/reading/writing or, that with enough time, they will improve as they get older. However, research shows that this is often not the case, and it certainly doesn’t happen for the student with dyslexia (Shanahan, 2020) . Instead, the gap gets wider, thereby gradually affecting not only their academic skills, but their self-esteem and confidence as well. Early identification and intervention are, therefore, key to unlocking the potential of individuals with reading/writing challenges or dyslexia.

So what type of intervention specifically assists students with dyslexia?

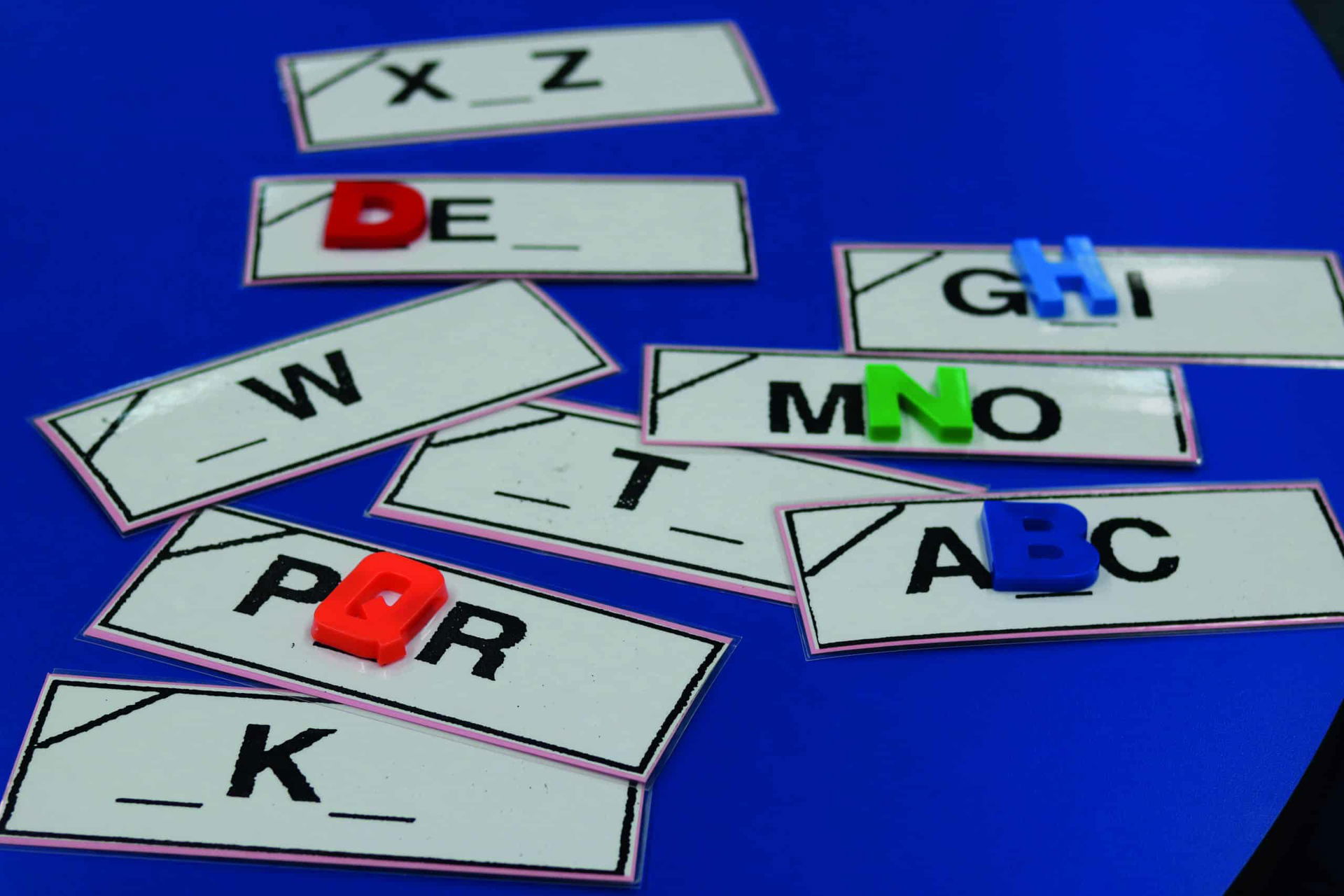

As soon as a parent/teacher notices a child is having reading/writing/spelling difficulties (beyond the developmentally appropriate), a necessary starting point is identifying the ‘gaps’ that are present. With this information, a rigorous (research-based, and explicit) programme should then be used to increase their skills. In addition, this support should be regular (preferably, daily) and targeted, as students with dyslexia often require multiple exposures/explanations compared to their peers. Individuals with dyslexia also benefit from ‘multisensory’ approaches to learning – i.e. one that uses more than one sense to explain a skill/concept (Birch, 2018).

Understanding the students’ learning journey, showing belief in their skills and talents is another important point to make. Many students with dyslexia possess originality and creativity beyond the ‘regular’ and it is our responsibility as parents and teachers to shine a light on these talents, whilst also helping them develop their literacy and numeracy skills.

I think my child is struggling in reading and writing – what should I do?

After the challenges of Covid-19, many parents have noted that their children are having difficulties with reading and writing. Therefore, a good starting point would be to talk with the child’s class teacher and/or learning support teacher, as they will also have a lot of information to share with you that will help. Working together as a team to assess the child’s challenges and plan a specific programme of support is a good beginning.

However, some students may need a programme that is more targeted, regular and explicit (e.g. the Oak Hill programme in Nyon). Whichever intervention strategy is used, it is important to measure its impact to assess what specific progress has been made by the student over time.

I want to find out more about reading/writing difficulties and dyslexia – do you have any suggestions?

Yes, there is a lot of useful research based information out there for parents and teachers to avail of. Here is a selection:

www.dyslexiaida.org – an international resource helping raise awareness about dyslexia and the best remediation techniques/programmes that can help

www.hillcenter.org – offering research-based training to support students with reading and writing challenges

www.readingrockets.org – this website has a lot of useful information for parents and teachers about reading, writing, and dyslexia

www.dyslexiatraininginstitute.org – offering training for parents and teachers

www.apmreports.org/episode/2019/10/23/hanfordandreading – the US journalist Emily Hanford offers some interesting thoughts about how reading is taught

To continue learning about the subject of dyslexia and reading, visit Oak Hill’s website for additional references/resources and/or details about upcoming seminars or open mornings.

Tricia Spencer, (B.Ed., M.Sp.Ed., M.Aut.Stds., M.Ed.Lea).

Tricia is the Head Teacher at Oak Hill, Nyon; a center of excellence for students with dyslexia and/or AD(H)D. In this half day setting, students between 7-14 years of age address their challenges in literacy and numeracy using research-based methodology. www.oakhill.ch

Tricia has experiences leading learning support departments in the UK, Saudi Arabia, Switzerland and Australia. She is a CERI Structured Literacy Dyslexia Interventionist and has trained in IMSLEC methodology.

Dr Jennie Guise, (MA(Hons), MBA, BSc(Hons), MSc, PhD, PGCPSE, AMBDA FE/HE, MEd, CPSychol, CSci, AFBPsS, FHEA, SpLD APC (Patoss), EuroPsy, CMgr (MCIM)

Dr Jennie Guise is a Practitioner Psychologist with extensive experience of assessing for Specific Learning Difficulties in Primary and Secondary Schools, Further Education, Higher Education and in the workplace.

Jennie has also worked in research, and now in applied practice as founder and Director of Dysguise Ltd (www.dysguise.com).

More from International School Parent

Find more articles like this here: www.internationalschoolparent.com/articles/

Want to write for us? If so, you can submit an article here: www.internationalschoolparent.submittable.com