Six steps in changing a school’s culture

How – or rather, why – would you take an academically successful, efficiently functioning school with a clear identity and turn it on its head? The International School of Lausanne is aiming to do exactly that by rethinking what it means to be an English-language international school.

English has been part of our identity since we opened in 1962 with just 7 students. The school’s original name was the English School of Lausanne, and though the name has changed to reflect the fact that it is now a truly international school with representatives of 67 nationalities amongst its more than 900 students, until recently English remained the main language of instruction and part of our ‘reason for being.’

That said, like many schools, we have watched the shift in language research as it has moved from considering multilingualism as an exceptional even hazardous phenomenon, potentially at the root of a number of difficulties such as cognitive overload, semi-lingualism and language confusion, to something that provides learners with a strategic advantage. Speakers of multiple languages learn further languages more easily – they seem to have a higher metalinguistic awareness (in other words, they show a better understanding of the nature of linguistic structures) and a more analytical approach towards the social and pragmatic functions of language. However, more interestingly, research suggests that speaking multiple languages makes you better not just at other languages, but also more creative and better at mathematics, science, or history.

For the school to step away from English, or rather to embrace a fuller understanding of language by launching a dual language programme, required it not just to bring about a change in curriculum or a shift in the staffing model, though both of these things were necessary, but also to embark on a change in culture. It is a process that the school is still involved in, but when it comes to an end we will have fundamentally altered part of the way that we as a community see, speak, and think about ourselves.

How then does one go about such a change? There are a range of management tools that can be used to manage projects such as this: the strategy canvas, directional policy matrices, and McKinsey’s 7 S model for example. Based on our experience, however, we would like to suggest six steps that can be taken as part of any such change in a school, whether that change is linked to language or to any other aspect of what makes a school what it is.

1. Think about your core values and what really makes you what you are

Our first team meeting on the subject looked at what we were setting out to do. Though it formed part of the implicit understanding of the school, the words ‘English language’ were not actually part of our mission statement. ‘Excellence’, ‘recognising the unique potential’ of our students and equipping them to play a ‘responsible role in a multicultural world’ were. English, we saw, was a pragmatic tool rather than philosophical choice. Also at the heart of our discussion was the school’s fundamental purpose. Absolutely it was there to help young people succeed individually, but it was also there to work towards a better tomorrow through the promotion of mutual understanding. If you don’t understand the complexity of language, our thinking went, you can’t understand the nuance of culture. Many conflicts have arisen from a lack of understanding of culture and nuance.

We went away to do some research.

2. Do your research

There are many good schools around the world and we felt that almost inevitably, possible solutions to our problem were being discussed elsewhere. We looked at research and, at other schools, there are a host of versions of bilingual education and we needed to understand what would fit in our context. We were aware that what might work well in another school or situation might not work well for us. We talked to heads of schools and classroom teachers about how their systems worked and thought about what elements of those systems we could import into our own. We also talked to our parents and students about how they saw the place of language. What we found was an enthusiasm, a willingness for change, and a conviction regarding the change that was surprising.

“As expats committed to settling in Switzerland, the opportunity for our child to be a part of a dual language pathway has opened up so many opportunities. When we asked our daughter why she would like to be involved in the DL programme she said ‘So when I go outside with my friends in the neighbourhood I can speak French with them’”

3. Frame your idea and articulate your goals

Having decided the direction we wanted to head in, we started talking to people so that they would understand why a change was needed. We brought staff together and helped them understand the reasons for the change and what role they could play in the process. We tried to ensure that people had multiple opportunities to contribute ideas for the implementation process, and to provide feedback or share concerns. We needed to determine our staffing early on because one of our design principles was that we wanted the teachers to shape and own the programme. For that, we needed to identify people willing to take on such a significant project.

4. Map out your plan

To address our specific community, rather than propose a fully bilingual approach, we decided to move forward with a dual language class in one or several year groups. The question then was which ones? There were a number of possibilities: research shows that early immersion students tend to achieve higher levels of oral proficiency than late immersion students. Conversely, research has also shown that students in later immersion programmes can achieve similar technical proficiency levels as those who were in early immersion programmes.

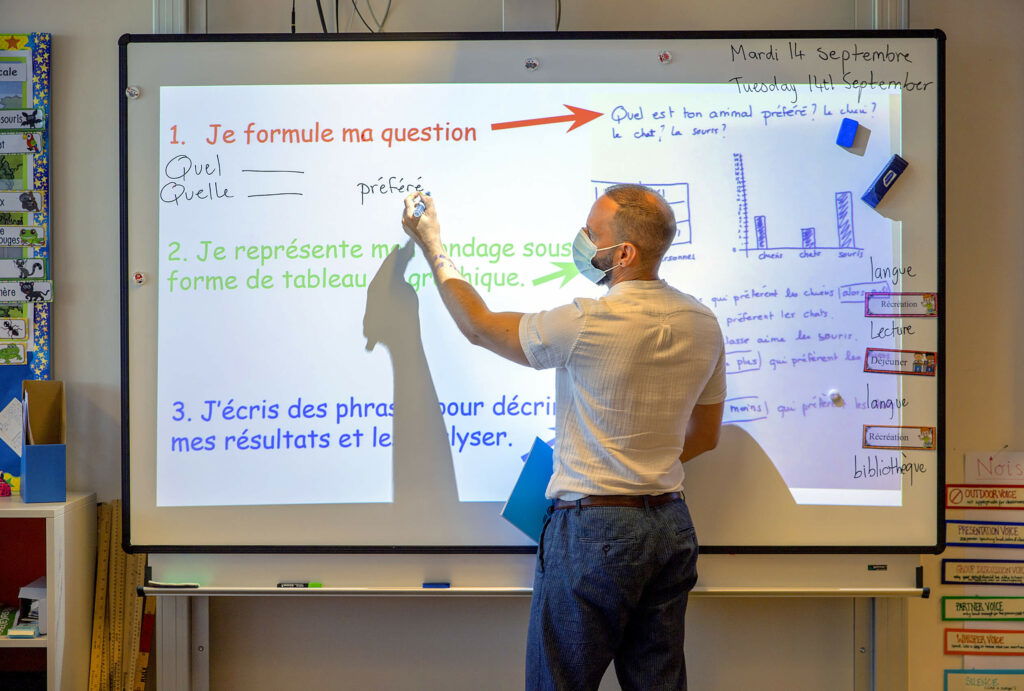

Our decision was to use a stepped approach starting with the launch of dual language classes in Years 4 and 5. This allowed us to have an immediate impact, offer choice to families (the other classes in the year groups would continue to be English dominant), and to be targeted in our curriculum development work. We planned for and made explicit the introduction of dual language classes in Years 3 and 6 the following year, and of a focus on language immersion in the earlier years so that there was a clear developmental pathway into the dual language classes.

5. Dedicate resources

It seems obvious but, as we were developing a new programme, we had to make space for development work to be done. The staffing model involved an anglophone and a francophone teacher working together in each class with a significant amount of co-teaching. In the six months before the start of the programme, these teachers were given weekly release time to co-create the future curriculum. Since the launch of the programme, we have also found that the co-teaching model has allowed teachers essential flexibility in their time to develop new resources and to adapt others. One of the most challenging aspects we have found is the need for the dual language teachers to both collaborate as a team and to continue to collaborate with their year group colleagues. Provision of both types of collaboration time puts significant constraints on the timetable.

6. Evaluate your progress

We are now well into the first year of the programme and are learning constantly. We have seen how important the work we did before the programme started was, and how important it also is to not be tied to how you thought something was going to go rather than how it actually goes when it is implemented. We have weekly team meetings to talk through our progress and half termly feedback opportunities for parents to let us know how they think the programme is going. We need to be flexible and receptive enough to change when things are not going well but not so flexible that we get blown continually off course. We have been lucky to be able to get a parent whose child is not in the Primary School, but who is an academic researcher in the field of multilingualism, to help us think about our progress and the classroom experience. A supportive but informed and critical friend is hugely beneficial.

Our two dual language classes in Years 4 and 5 are full and we are now in the second stage of the plan getting ready to implement classes in Years 3 and 6. Parental feedback is very good and there is already considerable interest in the new classes. Perhaps interestingly there is also a growing broader understanding of the place and importance of languages other than English at the school, the programme acting as a platform for us to consider how we raise the capacity of French throughout the school.

A key learning for us has been the benefit of creating a framework that is highly responsive by having sessions that inform, engage and involve people so that they are part of the programme development. There are several things we might have done differently. One reflection has been that we did not spend sufficient time thinking about how the class might be seen by other parents whose children are not in the programme. We want the dual language classes to be seen as offering our PYP programme through two languages and not as offering something different that is only for the most able or the most linguistically adept. Overall, though, we feel that Einstein’s dictum, that if he had an hour to solve a problem he’d spend 55 minutes thinking about the problem and the remainder thinking about solutions, has proved to be a useful guide.

Frazer Cairns is the Director of the International School of Lausanne.

Stuart Armistead is the Primary School Principal of the International School of Lausanne.