The Power of Words: Building lasting behavioral change

By Dr. Laurence van Hanswijck

“Sticks and stones can break my bones, but words can never harm me”.

As a kid born in the 70s, this sentence was commonly thrown around. The intention is clearly to help a young person develop a thick skin. As an adult, I’m not convinced that this saying holds any value at all. No matter how you slice it, words can be incredibly hurtful. Not only can they be hurtful, but also, when properly placed, very powerful. Funny enough, when you look at certain words, you can see other words embedded in them. Have you ever considered that when you add an “s” to the word “word,” you have the word “sword”? Words can be swords.

However, rather than assessing words for the damage they can create, this article seeks to shed light on how we, as parents, can use words to create positive change in our children; how we can use these words to our advantage. Often, it is not our message that needs to change, but by changing one single word, the subconscious message and how our children interpret it can change the whole message. Neurolinguistic Programming is an entire field dedicated to subconscious influences and how our language can impact them. Similarly, therapies such as Dialectical Behaviour Therapy and Cognitive Behavioural Therapy understand the power of words. From these therapies, several words and messages warrant consideration. While not all will be revealed here, this article will address a few when it comes to behaviour modification or redirecting behaviour. Additionally, there are instances where using fewer words or no words at all can be more impactful, as we recognise that words can be superfluous.

“No!”

One word that is most commonly used, especially during the toddler years, is the word “no.” The word ‘no’ is crucial as it is a stopping word; it prohibits you from engaging in certain actions or moving toward specific things. It is important when a toddler is about to stick their fingers in a socket to keep them safe, it is short, fast, and effective. However, the word “no” is often overused in daily situations as a stopping word where a child is then left to think for themselves as to what now to do! For instance, when a child asks if they can watch tv and is met with a simple “no”, it becomes a blocking behaviour. Unfortunately, the child is then likely to persist in questioning, as they have not been provided with redirection. This can lead to escalation and meltdowns. Redirecting behaviour in a positive and effective manner involves more than just saying “no.” It requires clear communication, understanding, and offering alternatives.

Positive framing and offering alternatives. Instead of using a negative response like “no,” reframe your message in a positive light. For example, if someone is doing something you want them to stop, you can say, “I appreciate your enthusiasm, but let’s try doing it this way instead.” Alternatively, if they are met with “why don’t you go and draw or play Legos or build your fort instead”, they are now being directed to alternative activities which makes it more likely that they will give up on the TV line of questioning.

Providing Choices. Empower children by providing options to choose from, so they feels more involved in the decision-making process. This approach fosters cooperation and engagement. For instance, you could say, “How about you choose between option A or B. What do you think?”

“And” not “But”

Instead of using “but”, which can negate the preceding statement, use “and” to add another positive aspect into the conversation. For example, you might say, “I like your idea, and I think we can make it even better by…”. This is a concept central to Dialectic Behaviour Therapy (DBT). The term “Dialectical” means trying to understand how two things that seem opposite could both be true. For example, accepting yourself and changing your behaviour might feel contradictory. However, DBT teaches that it’s possible for you to achieve both these goals together. By understanding dialectics, you start to see that there is more than one way to solve a problem and that two seemingly opposite ideas can be true at the same time. The simple summary of a dialectic in DBT is to remember the power of “AND”. People often try to provide positive feedback followed by constructive criticism. However, when we say, “you did a good job on your homework, but you could still do better”, that completely negates the positive statement and the child is left with the fact that they should do better, feeling disappointed. On the other hand, saying “you did a good job on your homework, and you could still do better”, validates both statements and leaves the child feeling more hopeful. Look at the differences between these examples:

- I am disappointed in you, but I still love you → I am disappointed in you AND I still love you.

- I understand your point, but I am allowed to disagree with you → I understand your point AND I am allowed to disagree with you.

For those who are aware of the word “but”, they often try to replace it with various words to make it less negative, such as ‘however’, ‘nevertheless’, ‘conversely’, and ‘yet’ among others. These words have the same impact as “but” as they negate the previous statement. Using the word “and” will give you a positive outcome and a much more compliant child.

The “I”

There are a few important points to consider here. When you find yourself feeling upset with your child and formulate a statement along these lines “You make me feel upset when you ignore me while I am talking,” the likely outcome is putting them on their backfoot, and an argument could ensue. The problem with this sentence is that it implies that the child made the parent upset, which places blame on the child. However, from Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT), we learn that our feelings do not depend on what the other person said or did; instead, it is what we think about what the other person said or did that makes us feel our strong feelings.

This concept is truly empowering, as it means that we are in control. While we cannot change what someone said or did, we do have the ability to change our thinking about it. This is a powerful understanding as it means that the other person is not in control of us. For instance, if I were to think, “Johnny is so rude, he can’t even be bothered to listen to me, he clearly doesn’t care about me”, I clearly am going to feel quite upset. However, if my perspective shifts to “Johnny is a typical teenager, probably has important things on his mind like exams or friend problems”, that would be equally true and such a perspective would lead me to feel calm and perhaps approach the situation in a different way.

The moral here is that we own our feelings as we own our thoughts; thus, it isn’t really Johnny who made me upset. The statement “you make me feel” does two things; it disempowers me as I am giving my power away of owning my feelings, and secondly, it is blaming so will put Johnny on his back foot. Johnny likely wasn’t trying to upset me; he was lost in his teenage thoughts (perhaps!). The alternative statement “when you ignore me while I am talking to you, I feel upset”, would give a different outcome. Johnny would not perceive it as blame, and understand that the feeling lies with me.

If you can express your experience in a way that does not attack, criticise, or blame others, you are less likely to provoke defensiveness and hostility, which tends to escalate conflicts. It also helps prevent the other person from shutting down or tuning you out, which tends to stifle communication. Ultimately, using ‘I-messages’ help create more opportunities for the conflict resolution by creating more opportunities for constructive dialogue about the true sources of conflict. Taking it one step further, these are the steps to a more collaborative outcome and reduction of conflict:

1. “When you__________________________________________” state observation

2. “I feel, or I think ______________________________________” state feeling

3. “Because ___________________________________________” state need

4. “I would prefer that___________________________________” state preference

Instead of saying: “I hate when you yell at the kids.”

Say “When you yell at the kids, I feel angry because I need the kids to be treated with respect. I would prefer that you not raise your voice or curse in their presence.”

This approach does not put the child on the back foot as they are not being blamed; it explains the need and offers a solution. This is where a conversation starts rather than being met with a shutdown or an argument.

You are

This aligns somewhat with the concept of “I statements”, this is where we associate a behaviour with a child’s character, unknowingly. Many of the statements we make are not what we intend them to be, however, they embed into a child’s subconscious in ways we did not anticipate. This creates a situation where the behaviour change decreases as the child seems to give up. The way in which we communicate can leave a lasting impact on their self-esteem, emotional well-being, and their willingness to learn and grow. We will often have to correct our children; this is part of parenting. It’s important to distinguish between criticising the behaviour itself and criticising the child as a person.

When we try to separate the behaviour from the child, it becomes more likely to effect change without adversely affecting our child’s belief in themselves or self-esteem. For example, when a child has a messy room and we say, “look at this room, Johnny, you are so messy and careless”, it implicitly indicates to the child that they are messy, and that is a character trait which can’t be changed. As such what happens is that Johnny is less likely to clean his room and more likely to believe the premise that he is messy resulting in lower his self-esteem and efficacy. However, when we say, “Look at this room, Johnny, you are being messy”, all we changed is “you are being” from “you are”, we changed one word. This one-word change conveys a different message to the child. Now, it reads as a behaviour that Johnny is having, and Johnny implicitly understands that it’s a behaviour that can be altered. Consequently, he becomes more inclined to make the change. One step further is to be more specific, e.g., “Your toys are scattered all around your room; people can trip over them. Have a look at finding a better place for them”. This takes all the emphasis off Johnny’s character, explains why this is a problem, and offers a solution. One step further is to ask Johnny how he plans to solve this problem. If he can’t come up with an answer, you can suggest a couple of options for him to choose from. This final step encourages accountability since suggestion came from him, so he is more likely to do it and continue to do so.

Specific Praise

From the work of Dr. Dweck, we now universally recognize the importance of the development of growth and fixed mindsets. We now understand how greatly important praise is in fostering a “can do” mindset. Such a mindset encourages persistent effort, willingness to tackle greater challenges, and personal growth. We can create permanent change by being specific in our praise as to what it is we want to encourage. This encourages the person to continue the behavior you want to see. For example, you might say “I really liked how you handled [situation]. Keep up the good work!” Or for those kids that struggle to sit for long, if they manage to sit for a given time, you could offer praise like “wow, you did such a great job at sitting for x amount of time, keep it up”. In doing so, the encouragement goes towards the child’s action, and the child will focus more on that action in the future. Likewise, this praise holds true for any work, homework, action, etc. that the child performs. Always make the praise about the content and not an ability praise. Praise that emphasizes innate abilities, talents, or static qualities can contribute to fostering a fixed mindset, e.g., you’re so smart, you’re so talented, you’re a natural, you’re the best. Praise that promotes a growth mindset, on the other hand, emphasize effort, improvement, learning, and resilience. E.g., “I can see how hard you tried on these sums, your effort really shows”, “I love how you always ask questions, that is how you learn and grow, keep it up” etc. It’s about getting specific. Inadvertently, it also fosters a sense of connection. Because the praise is so specific, the child perceives it to be genuine and this means you have paid attention to them. At first, it is harder than giving a blanket statement, but it becomes easier as you practice. It also is rewarding as you see your child continuing to strive, push themselves further and grow. One addition to this section on praise is, it has to be genuine! Kids (and even adults) can feel ingenuine praise and it will have the inverse effect!! Here’s an example:

Problem: Johnny never participates in class discussions.

Desired Behavior: Actively participating in class discussions.

Praise: “I really appreciate how you shared your thoughts, Johnny. Your input added a lot of value to the discussion.”

A final note

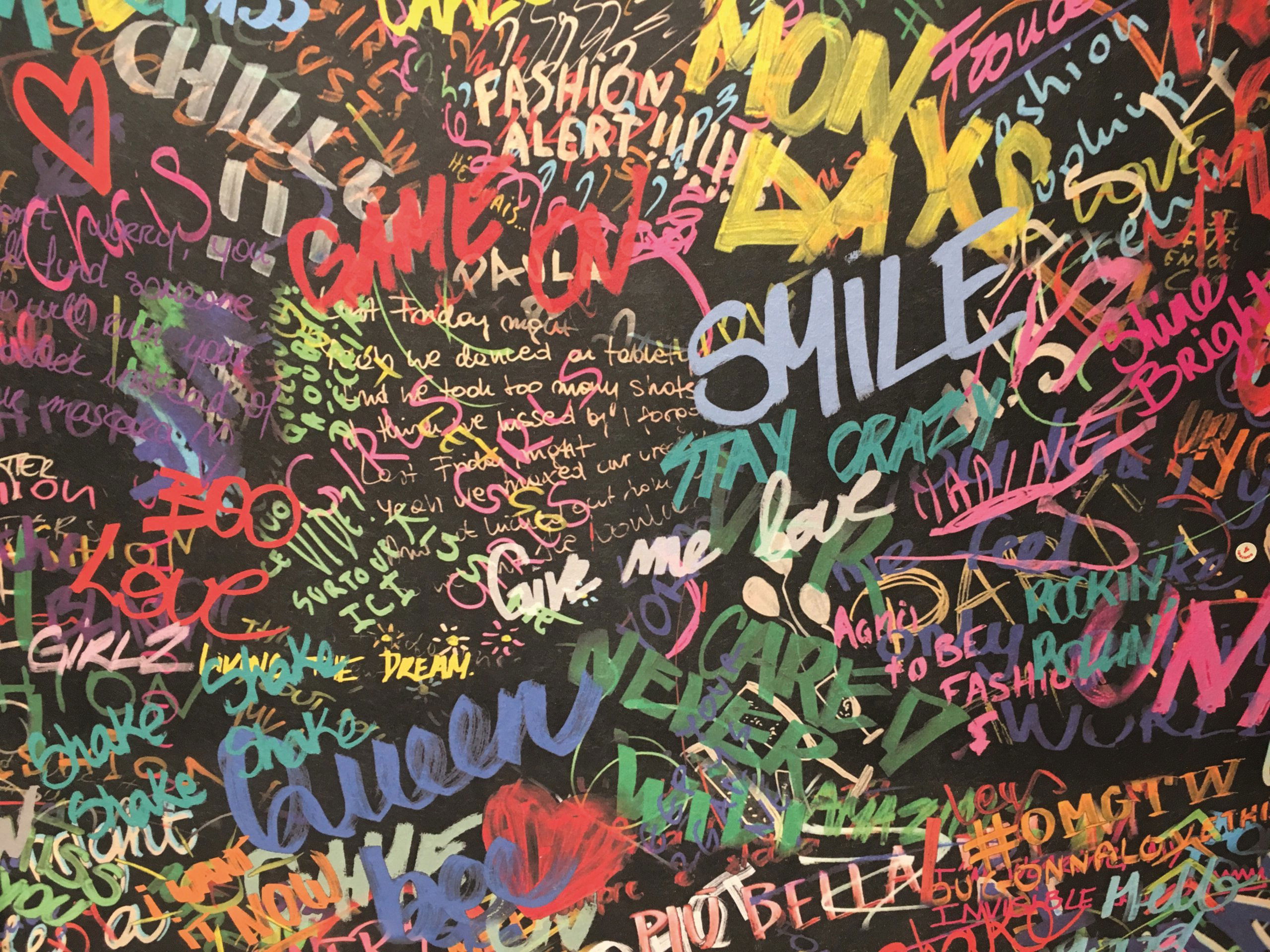

Words are important and can greatly impact lasting behavioral change. The way we deliver these words are equally important! Studies have shown that in communication, a speaker’s words are only a fraction of their efforts. The much-quoted work by Prof. Mehrabian quantifies that words account for 7% of personal communication, while tone of voice, and body language respectively account for 38% and 55% respectively. For instance, If I said “wow that is such good use of colours, Johnny” in a monotone voice, looking at the floor with my arms folded, how would that land? It would likely be quite confusing and not be met with much belief. Children are more sensitive to nonverbal cues and emotional signals, and these elements can greatly influence their understanding, behavior, and the quality of your relationship with them! Often, parents don’t need words to communicate their thoughts to their children. I have a few pictures of grannies and parents looking at their children/grandchildren with expressions of complete adoration, it is hart warming to capture. No words are needed; the child captures that look and responds with a smile, it is imbedded deep in their brain, they feel loved. Smiling at your children has a direct impact on their limbic system, the brain region responsible for processing emotions, social interactions, and bonding. Smiles are one of the earliest forms of nonverbal communication that infants respond to. When you smile at your children, it triggers feelings of attachment and emotional bonding. The words “I love you” actually do not mean so much without the look or the touch, the hug or the tone.

We all do some of these things naturally in our day-to-day lives. This article hopefully adds some tools to your toolbox. We all need tools in our toolbox and some of these tools are mighty handy as we navigate parenthood without the proverbial manual that our child should have been born with.

- Mindsets: How Simple Changes In Praising Can Influence Accomplishment And Motivation

- “I feel how you feel…” The importance of helping your children to develop empathy

- How to write a great university application

- Help! My child is a social media expert, how can I keep up?

- How can I tell if my teen is struggling with their mental health?