What is in a name?

Plants have Latin names and common names, but if you’re new to gardening and plants, why might you want to learn both? Common names are great, and can give insights as to how the plant might have been used in the past, like the brilliantly-named “wolf’s-bane” for the extremely poisonous plant, Aconitum, the juice of which was used to tip arrows for hunting wolves, or “soapwort” which, when boiled, makes a soapy liquid that is good for cleaning delicate fabrics.

However, we often find that common names are duplicated and used for different plants. A bluebell, for example, could refer to a spring-flowering bulb, Hyacinthoides non-scripta, or to a summer-flowering perennial, a Campanula. This is particularly difficult when talking about plants from other regions, or to someone who is from another part of the world, as the common plants will not be the same. Imagine how complicated it is when talking to someone who is not a native speaker, or, like in Switzerland, where there are several languages to add to the confusion. The simple solution is to get to grips with the Latin names of plants. Latin names are the same for every language, and for every speaker. The names don’t change (or not very often, and only in agreement internationally) and can give a clue as to the plant’s habitat, where it comes from, when it might flower and all sorts of other information.

The Latin names we use today are thanks to a system devised by the Swedish biologist, Carl Linnaeus, in the 1700s. He created a system to classify all living things, and he divided them into the kingdoms of animals, plants or minerals. If you’ve ever played the guessing game called Animal, Vegetable or Mineral, you will already be familiar with these divisions.

The urge to classify and organise, which you might do by making a playlist, or putting all your sweaters on one shelf together, is part of how humans try to understand and order the world around them. We have records of attempts to classify plants from over 2000 years ago. Theophrastus’ “Historia Plantarum” was published around 300 BC and attempted to group plants together, based on how they reproduced, as well as to explore their uses. His work was still in regular use in the Middle Ages, and Linnaeus referred to Theophrastus as “the father of botany.”

In between Theophrastus and Linnaeus, there were many different attempts at creating a universal system of classification, including the French botanist de Tournefort in the early 1700s, and John Ray, an English naturalist, the century before. All of these systems used observation, either of the habitats of the plants and animals, or their appearance, such as counting the petals on a flower. The Linnean system used many of these previous works, and combined it all into a unified and simple whole. Every living thing had two names (called a “binomial” or two-name system) and both names are always in Latin. The first name was the “generic name”, the genus or group to which that living thing belongs, like the word Canis for the group that includes dogs, wolves and jackals. The second name is a specific epithet (for plants, bacteria and fungi) or a specific name for animals. This might be a word like a colour, or describing the preferred habitat of the plant of animal, or where it comes from. If you see the note “L.” after a plant or animal name, you know that it was named by Linnaeus himself.

The words chosen for both the genus and the specific epithet can come from all sorts of places. Latin and Greek are the most common, but you will also find medieval words, modern names, geographical names and even anagrams. The specific epithet, the second part of the name, in particular, helps to give a clue about the plant. You might find “odoratus” for a plant with a lovely perfume, or “foetidus” for one that stinks. I find that researching the origin of the plant name helps me to remember the Latin name. The beautiful, but trickily named Chimonanthus praecox, takes its name from the Greek “cheimon” meaning winter, and “anthos” which means flower, plus the Latin word “praecox” which means very early. It flowers in January, which is very early winter flowering, so it fits its name perfectly.

The lovely spring-flowering bulb, Fritillaria meleagris, shown here, gets its name from the Latin for a dice box (“fritillus”), and the word for a guinea-fowl in Greek (“meleagris”) which has delicately spotted feathers. The flower is a cross between the two, if you look, the spots are actually squares.

The brilliant “Stearn’s Dictionary of Plant Names for Gardeners” by William T. Stern is an excellent source of information for the curious. It was last reprinted in 1992, so you can often pick up second-hand copies for under 20 francs on line. It’s a great addition to any home or school library.

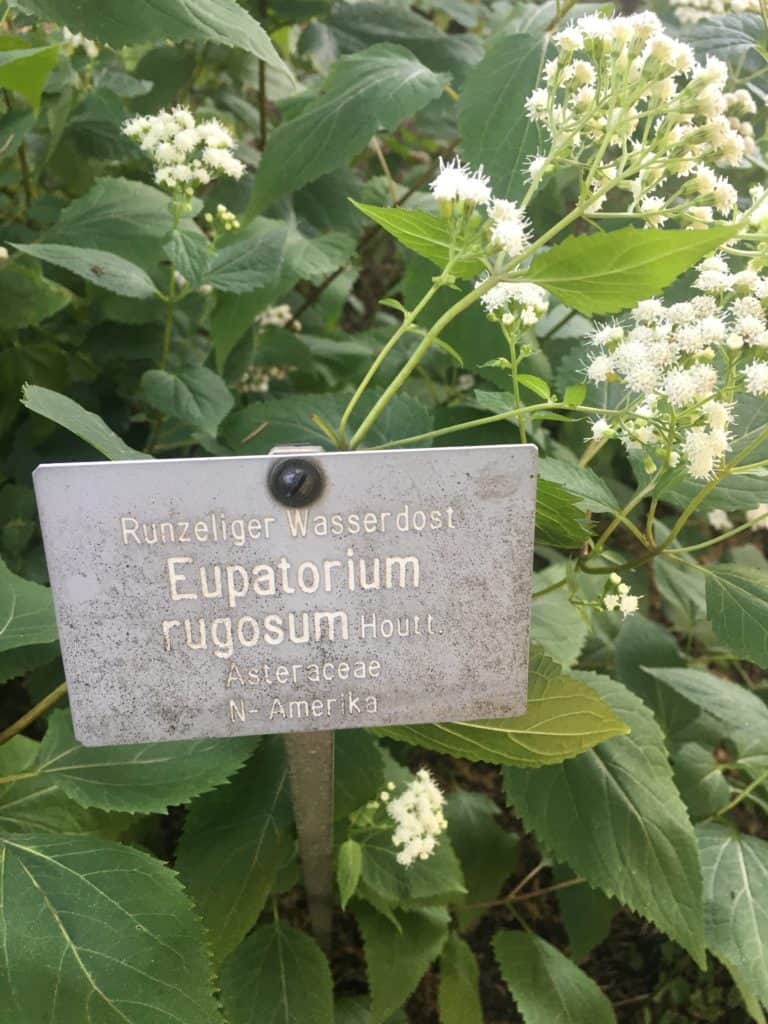

Next time you go to a botanic garden, take a closer look at the plant names on the labels. There is lots of information there. This one is from the Botanic garden in Bern, and you can see that the first name on it is the common name in German. Next is the Latin name, with the person who named it, in this case Maarten Houttuyn, a Dutch naturalist, whose name is shortened to Houtt for plant naming. The label also tells us which family the plant belongs to, the Asteraceae, the daisy, aster and sunflower family, so we can make a guess about what the flowers will look like. Finally, it tells us what region of the world it comes from, which helps to understand what kind of conditions it likes to grow in.

Plant names are decided by the International Code of Botanic Nomenclature, and can only be changed by an International Botanical Congress. Names might be changed because a new plant has been discovered that makes previous decisions retrospectively incorrect, or, more usually, because DNA analysis has shown that the plants in question are or are not closely related to each other. A recent example is the change of Latin name for rosemary, a common garden herb, from Rosmarinus officinalis, to Salvia rosmarinus. Rosmarinus comes from two latin words, “ros” which means dew and “maritimus” which means, of course, connected to the sea. It is often found growing wild on cliff edges in southern Europe, and is also a popular garden plant. The “officinalis” part of the name means simply that it is sold in shops, from the days when herbs would be kept in an “officina”, a store room in a monastery, and was given by Linnaeus to any plants that had an established medicinal or culinary use. Salvia is the name for the sage family, the name comes from the Latin word “salvere” to mean to feel well, and is connected to the word “salus” which can also mean well-being or prosperity. So rosemary becomes a plant that brings health and is connected to seaside dew.

How do you classify things? In my study, I have dozens of books about plants. I group them by subject, but I could equally have classified them by author, date of publication or even the colour of the cover! How might you go about classifying plants, if you weren’t going to use the Linnean system? By size, by colour, how many petals, what they taste like? There are many projects you can do with kids of all ages, to bring the subject of classification to life. Start by collecting as many different leaves as you can from your garden or around your school. For younger kids, get them to decide how they should be divided up – big leaves and small leaves, or shiny leaves and soft leaves? For older students, they can look at areas like vascularity, or leaf shapes. Careful observation and note taking are essential for this activity. Who knows, perhaps you’ll come up with a new way of classification to beat Linnaeus!

More from International School Parent

Find more articles like this here: www.internationalschoolparent.com/articles/

Want to write for us? If so, you can submit an article for consideration here: www.internationalschoolparent.submittable.com