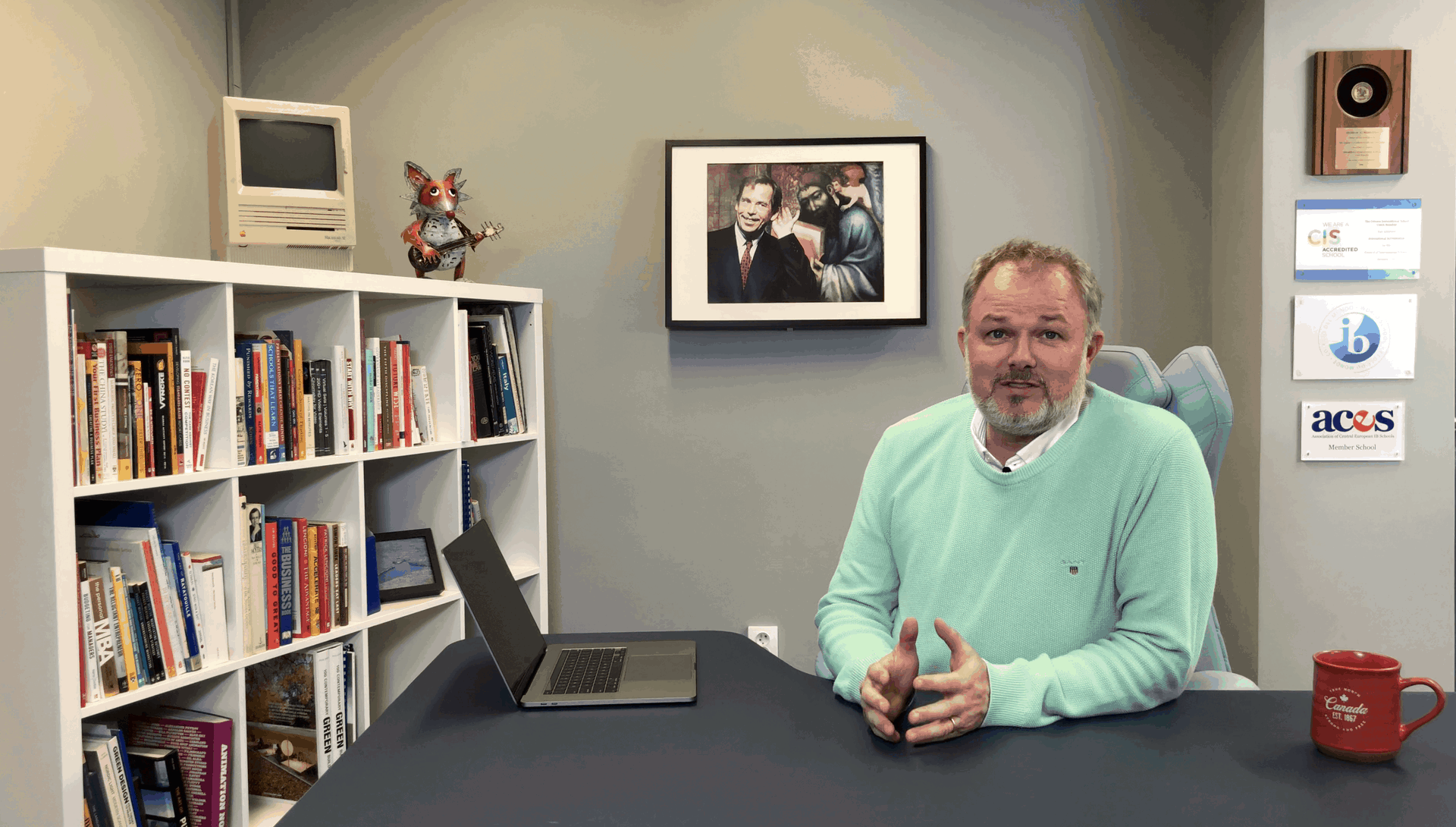

Meet Brett Gray: Founder and Director, The Ostrava International School

In the Moravian-Silesian Region of the Czech Republic, a visionary Canadian leads a multi-cultural community of learners in the country’s first authorised International Baccalaureate Continuum School. The Ostrava International School (TOIS), founded by Director Brett Gray in 2008, is the culmination of over 30 years of dedication and love for a place at the coalface of sweeping late-20th century cultural and political changes. The school offers an internationally recognised programme for learners, emphasising academic challenge, open-mindedness and respect.

ISPM talks to Brett Gray about his journey to creating an educational beacon in post-communist Czech Republic and his vision for a school that encourages students to discover, connect and achieve.

Tell us a bit about your background and what inspired you to become a teacher.

The truth is that I never thought in a million years that I would ever become a teacher.

My educational background is in Broadcast Journalism and French from the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. As a teenager, I was deeply interested in human rights. I wrote my university admissions essay on how I would like to be part of helping to free Nelson Mandela and bring down apartheid in South Africa through reporting and honest journalism. That was in case Plan A – become a professional baseball player – fell through.

In my junior year of university, I joined a study-abroad programme at the Sorbonne and Sciences Po in Paris. This was in 1987, and I spent that Christmas break going through Czechoslovakia and Hungary by train to have a peek behind the Iron Curtain. Perestroika was rumbling, but the people I met were still very closed – cautiously curious, but not in a position to communicate openly. It was a considerable risk for them. The impending collapse of communism across Central and Eastern Europe was certainly not on anyone’s radar at that moment.

Fast forward to the fall of 1989: communism was crumbling, and I was fascinated. Back in Los Angeles to complete my university degrees, I had become inspired by Czech writers, especially Václav Havel – playwright, philosopher, and general thorn in the side of the Czech Communist Party. With books like Letters to Olga, Open Letters, and the Power of the Powerless, written from prison and addressed to his wife, the country’s leadership, and ostensibly the whole world, Havel led me to a greater understanding of the importance of Civil Society, and how, without firm democratic principles and mechanisms in place, none of us can be free.

By December 1990, I was the proud owner of two freshly-minted university degrees and hungry to be a part of a democratisation process that seemed to be happening all over the globe. In January 1991, I decided to spend some time in the country that had just re-cast its playwright-philosopher into the role of President of Czechoslovakia. I wanted to write first-hand accounts of the social, economic, philosophical, and ecological impact of the country’s transition to democracy. Maybe to teach a little English on the side to help pay the bills, for a year or maybe two.

Well, it is thirty years later, and I am not writing news articles, but leading The Ostrava International School, an organisation that promotes academic excellence, with a mission and core values that are tightly aligned with the principles of the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights and the International Baccalaureate Learner Profile.

I would like The Ostrava International School to be a place where students develop an interest in making the world a better place.

What were your experiences of teaching when you first arrived?

When I arrived a little more than a year after the fall of communism, there were many mixed feelings about the West. There was fascination and a strong desire to see what was out there. But there was also some trepidation about what the West would bring. For whatever reason, as a Canadian, I was warmly welcomed in the small town where I began to teach at a Czech gymnasium, which is a secondary school that prepares students for university.

I found an education system that relied almost entirely on rote memorisation. In this pre-internet age, knowledge was quantified, approved by the authorities, and delivered from the teacher to the student. The kids (and their parents) were afraid of openly expressing their thoughts for fear of getting into trouble.

This was about as far away as you could get from the teachings of the country’s famed native son and internationally recognised “Teacher of Nations,” Jan Amos Comenius. He had laid out 500 years earlier an approach to teaching that heavily emphasised learning through play. Statues of the famed pedagogue dot the Moravian-Silesian Region, but you would never know why judging by the school system’s organisation in the 1990s.

The school had almost no English language resources to speak of, except for the ever-present “Angličtina pro-Jazykové skoly”, a series of textbooks that local schools had used for years. They were tightly edited by the state authorities to ensure adherence to the political ideology that had recently come crashing down. Each chapter consisted of a text revolving around the semi-moronic-but-happy-to-live-under-socialism Prokop family; Mr Prokop was a satisfied factory worker. Mrs Prokop was a housewife. Their son was clever. Their daughter was pretty. Mr Prokop expresses his gratitude for living in a socialist country where people do not have to live homeless under bridges, like in the UK.

In terms of anglo culture, the books also contained hundreds of pages of debatably informative facts, everything from the colours of mailboxes in the UK and the US, to the names of a few British composers, or a strangely select group of English and American authors, from Shakespeare up to the 1950s, and lots of other government-approved bits of knowledge that were deemed appropriate for English learners to memorise.

It occurred to me fairly early on that many adults communicated with each other in a similar way. Rather than engaging in a discussion or exchanging ideas, conversations are more of a process of exchanging and counter-facts past one another.

But the kids generally pined for something else. In the first couple of years, two brilliant students were excellent at Maths and Physics and dared to dream of studying in the United States. We spent a lot of time working on essay writing and practising SAT and ACTs. When the results came in, one student was offered a full scholarship to Princeton for Physics, the other a full scholarship to study Mathematics at the University of Chicago. At that moment, I felt like I had found my purpose in life.

And yet, I would also see some of my best students fail to pass entrance examinations at Czech universities because they had neglected to memorise the names of four specific British composers listed on some page buried within the hundreds of pages of the Happy Prokop Socialist Bible.

Over the years, I began to struggle more and more with the Czech education system’s resistance to modernisation, its continued reliance on facts, and its lack of emphasis on developing skills.

So, in the late 1990’s I began to look for other things to do. I felt I had to move on from teaching for a while.

So how did you come to start The Ostrava International School (TOIS)?

As my frustration with teaching in the Czech education system grew, the City of Ostrava and the Moravian-Silesian Regional Authority reached out for help with re-working some of their promotional materials. They were trying to attract foreign direct investment into the area and wanted to polish their presentations.

At the time, their promotional materials were an obvious by-product of the education system. Long lists of undigested facts, most of which were either unuseful to potential investors or even downright off-putting.

I was eventually asked to make actual presentations to visiting companies, investment funds, banks, and other potential investors to speak as a Canadian living in the region for the last decade. After several close-but-no-cigar negotiations, we were told by CzechInvest, the State authority helping to guide foreign direct investment into the country, that Ostrava had lost out for one main reason: No international school.

It was a classic chicken-and-egg situation. There were no international companies because there was no international school. And there was no international school because there were no global companies. So, how to break the cycle?

Naively, I jumped in, thinking it would be an exciting project – for a year or maybe two.

After several false starts, I finally teamed up with two partners, Iva Konevalová and Jan Petrus. We finally managed to launch the project: an international school that would support both ex-pats and Czechs in the Moravian-Silesian Region. Our first-class of 16 Czech 15-year-olds began in 2005. After several years of operation, we concluded that our clientele, which was starting to include non-Czechs, would be best served by establishing two separate schools working together.

The Czech gymnasium we started would continue to serve Czech students, with many subjects in English mainly, but using the Czech state curriculum. Graduates would receive the Czech Maturita, and the braver ones could also sit for IB DP certificates or the IB Diploma. It would be a symbol of what a progressive Czech school could accomplish. But, because of limitations imposed by the Czech system, it would not primarily serve the foreign community.

The other school would focus on meeting the needs of the city’s growing international community. As readers of International School Parent know, there are many issues specific to the international community that need to be addressed, including adaptation, student well-being, the curriculum, mother tongue support, and on and on. The purely international school would be fully accredited by the most recognised international accreditation agencies and deliver the entire International Baccalaureate Continuum.

Tragically, both Iva and Jan died within a few years of the creation of the second school. From April 2012 until last year, I did my best to lead both of these schools as Executive Director and firmly establish their identities. In February 2020, I left the Czech gymnasium to entirely focus on the continued development of The Ostrava International School.

What is your vision for The Ostrava International School?

For me, an international school is a place where everybody feels safe being who they are – however different that might be. As someone who came here 30 years ago with little knowledge of the language or culture, I can empathise with the children coming through our doors. We all need a safe place to encounter others. That is the first step to breaking down barriers, gaining respect for yourself and the people in your community, opening up to the wondrous possibilities out there, and developing resistance to a world where differences are increasingly used to spread fear and hatred and, ultimately, ignorance.

The school celebrates the simple and fundamental idea that each of us has rights and responsibilities to enjoy freedom and equality. We can interpret things differently and follow different paths and belief systems. I would like our students to have the tools to move beyond pointing fingers and accusing “the other,” which seems to take up so much space in our public forums these days.

As our Guiding Statement declares, we strive to create a caring community of lifelong learners, each equipped with the knowledge and skills to succeed in an ever-evolving world.

How are these founding principles reflected in the curriculum? What does the school offer academically?

As an International Baccalaureate (IB) World School, we are part of an academic community that emphasises the balanced, holistic growth of the child. We strongly believe that when learners are in safe, respectful and supportive environments, they feel free to engage in a more meaningful way.

I am a firm believer in learning through meaningful play and discovery – essentially empowering a young person to be motivated in their learning, as an individual or as part of a group. One of the things that I love about the IB Diploma Programme for older students is the mandatory core subject called Theory of Knowledge. Students analyse how we know what we think we know and consider truth and fallacy. DP students also write a 4 000 word essay on a topic of their interest that must be meticulously researched, using internationally recognised MLA citation guidelines.

We’re very proud of the fact that TOIS is the only school in the Czech Republic authorised as an International Baccalaureate Continuum School, offering the Primary Years Programme (ages 3-10), the Middle Years Programme (ages 11-16) and the Diploma Programme (ages 17-19).

Academically, the results of our IB Diploma Programme graduates are consistently above the world average.

What makes TOIS so unique? What do your students and parents value most about the school?

We asked the TOIS community of students, parents, staff and supporters to reflect on our Mission: Discover. Connect. Achieve.

Across the board, our students, parents and staff said they feel the school provides a welcome and safe environment. Regardless of their English level, students reported that they feel little or no barriers to Discovery and are learning even to enjoy making mistakes, try new directions, re-build, and see what is out there.

The idea of Connection resonates strongly with everyone; connecting discoveries with previous knowledge; connecting socially with people who are different from me; feeling a sense of belonging to the group or the wider world. We constantly hear from parents how impressed they are with their children’s progress in developing their ideas and opinions. Parents also appreciate the school’s honest effort to keep the doors of communication open and bridge potential cultural and linguistic barriers.

In terms of Achievement, students consistently bring up how refreshing it is not to be taught to the test and to have the opportunity to show what they know. We strive to empower students to make meaningful progress from whatever points they started from. Students and parents have told us that this is highly motivating and almost always leads to deeper understanding and more meaningful achievement than simply studying to get the highest possible number of points. The proudest moments for us are when we are told variations of “I see my child growing and learning and doing things in ways that I couldn’t do when I was my child’s age” and “I see a level of critical thinking and self-reflection that I didn’t grow up with.”

It’s lovely to see our students’ development and achievements, and our philosophy of learning within a safe, respectful and supportive environment brings about positive outcomes and strong academic results.

How has the Covid-19 pandemic affected your teaching methods?

We have been impressed by the power and variety of online tools available to enhance learning, and I am sure that we will still be using many of them in the post-pandemic teaching environment. We’re exploring how we might use the flexibility of concurrent teaching (simultaneously teaching to students in the classroom and online) as a permanent fixture of the TOIS Curriculum. This could be of great use to students at home ill for more extended periods or for our high-performing student-athletes who may be training or playing in tournaments outside of the Czech Republic regularly. It has been interesting to observe the overall buy-in from the staff, as every one of us has had to improve our online skills quickly.

That said, I think there has been a considerable increase in the awareness of how we as humans are social beings and the damage that isolation under the COVID restrictions has caused. We’re excited about integrating technology further as a school, but there is no comparison to face-to-face learning and connection.

And in regular times, what sort of extracurricular activities do you offer?

We think it’s essential to keep our students active and engaged in activities that are not directly linked to the curriculum but complement their learning and help develop new skills.

We actively survey our students during regular times about the kind of extracurricular activities they would like to participate in. So the choice of clubs can differ from term to term and year to year. We regularly provide team sports like basketball and football, but there are all kinds of Clubs for Visual Arts, Performing Arts, Crafts, Chess, Lego, Robotics, Languages, etc.…

During COVID, students from across the school established and published the bi-monthly student magazine, Crispy – and I think it’s actually better for having been established during COVID because everyone’s computer and graphics skills have improved dramatically.

What are your hopes for students graduating from TOIS?

They will say that TOIS gave them the tools, motivation, and conviction to follow their dreams and turn their goals into reality. I also want our students to find common ground with, and mutual respect for, the “others” of the world, see opportunities for greater collaboration, and stand up to those that would threaten it.

What do you think the challenge is for education going into the future?

To not allow the entire system to collapse from information overload. Schools must be wise in choosing what can be thrown out of their curriculum to make way for what is needed. To allow children some quiet time for reflection and finding themselves. To continue to empower kids to be skilful and capable of dealing with the technological challenges coming up and still have a meaningful moral foundation or belief system about the kind of world they want to live in.

Having lived in the Czech Republic for 30 years now, what’s your take-away about the opportunities it has to offer?

I am grateful for having been given a chance to give something of myself that has been meaningful to others. In some small way, I have been allowed to change some lives for the better and make a small corner of the Czech Republic a better place than when I first came here. Living here has given me the chance to be a better person, fight for what I believe is right, reflect on my mistakes, and move on.

Most importantly, it has given me three beautiful boys and an extended family of beautiful people who love me and support the adventure of creating an inspirational international school in Ostrava.

Find out more about the school on the internationalschoolparent.com website or here: tois.world